Follow the Leader

The cobia (Rachycentron canadum) is the sole member of the family Rachycentridae. The species is distributed worldwide; in the western Atlantic, it ranges from Massachusetts to Argentina. In Florida, cobias occur in coastal and offshore waters and, less commonly, in the lower reaches of estuaries.

While cobia is the preferred common name, along the Gulf Coast, particularly in the Florida panhandle, it is often called ling or lemonfish. Because of its size (maximum 6 feet in length and 150 pounds in weight; normally seen under 50 pounds) and palatability, the cobia is a favorite among anglers and spear-wielding divers.

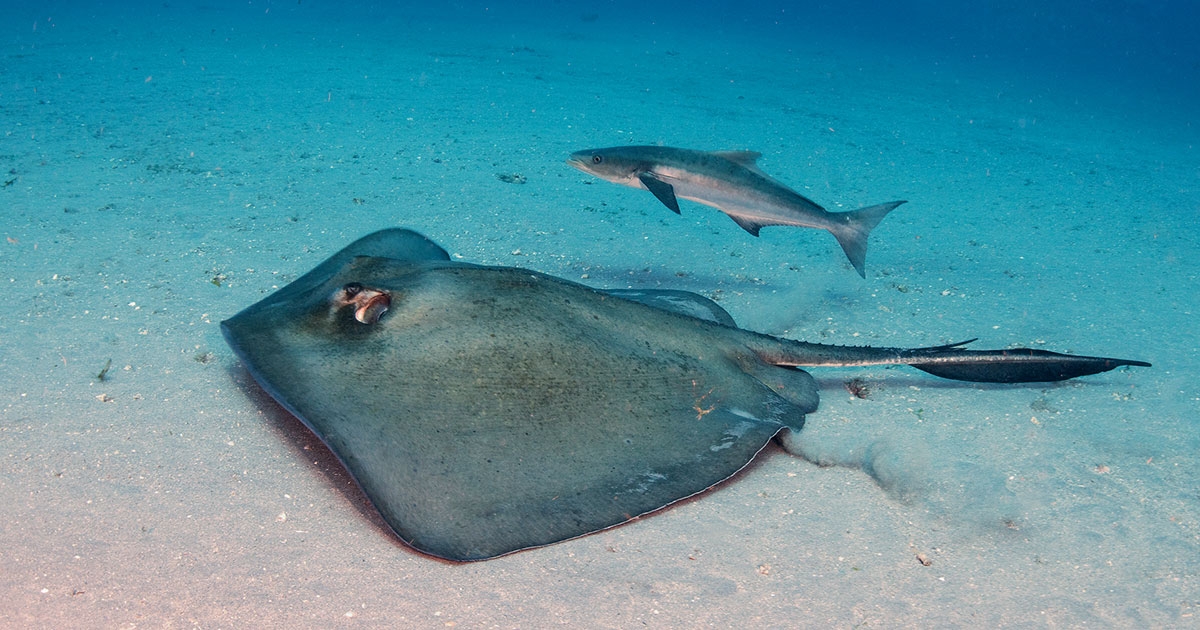

Cobias are migratory, and while underway they exhibit the interesting behavior of closely associating with large marine animals, especially sharks and rays (Photo 1). The cobia’s dark brown, torpedo shape and forked tail, high second dorsal fin, somewhat flattened head, small eyes, and broad rounded snout give it a shark-like appearance, an illusion not lost on divers observing one emerge from the bounds of visibility. When swimming, the large pectoral fins are erect. The dorsum is dark, the belly is white, and there is a prominent dark mid-lateral stripe edged in white. Individuals often display irregular patches of white along their flanks, head, and median fins.

In the waters off Florida and the Bahamas, I have observed cobias in the company of bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier), and whale sharks (Rhincodon typus); southern (Hypanus americanus) and roughtail (Bathytoshia centroura) stingrays; manta (Mobula birostris) and devil (Mobula spp.) rays; and leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). The first whale shark with which I had the good fortune to snorkel off Florida was flanked by a little band of cobias. The nature of this association does not appear to be obligate (required or hard-wired); such near-contact behavior by cobias may represent an evolutionary precursor to the direct physical attachment that has evolved in the closely-related remora (genus Echeneis), a fish that is similar in shape and color to the cobia (Photo 2).

Lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) covered with remoras, also known as sharksuckers (Echeneis naucrates), at Little Bahama Bank.

Lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) covered with remoras, also known as sharksuckers (Echeneis naucrates), at Little Bahama Bank.

Remoras are conspicuously distinct from cobias in that their first dorsal fin is modified into a sucking disk (Photo 3). Interestingly, cobias often host remoras.

Sucking disc modified from the dorsal fin on a sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates).

Sucking disc modified from the dorsal fin on a sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates).

Over the years I have seen cobias most frequently with large stingrays. The cobia’s affinity for following bottom-hugging stingrays may provide a functional advantage, as the rays displace meal-worthy demersal fishes and invertebrates from the seabed. In fact, examining the stomach contents of cobias caught from around stingrays reveals swimming crabs (Family Portunidae), sea robins (Prionotus spp.), small skates (Raja spp.) and flounders (Family Bothidae and Paralichthyidae), which are all bottom-dwellers.

Prey displacement explains cobia’s affinity for stingrays, but not the reason for them sidling up to planktivorous mantas and whale sharks or highly predatory tiger and bull sharks. Disentangling the evolution of this behavior as well as the genealogical relations with remoras will require some creative sleuthing from geneticists and behaviorists.

Corporate Headquarters

8502 SW Kansas Ave.

Stuart, FL 34997